Around the world, communities are rethinking how decisions are made — who gets to participate, whose voices count, and how power is shared. In this context, the Inclusive District Platform (IDP) emerges as a practical model to center people, equity, and consent at the heart of local governance.

The IDP is not a single tool or initiative — it is a collaborative framework for reimagining how local governments and citizens work together. Built on the foundations of data, dialogue, and rights, it creates the space for ethical, inclusive decision-making.

The Inclusive District Platform (IDP) is a decentralized governance model grounded in Elinor Ostrom’s principles of community-led management of commons. It is designed to complement the limitations of state and market systems by placing communities — particularly those historically marginalized — at the center of ethical, data-driven, and participatory decision-making. At the heart of the platform lies the integration of Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) as a foundational process for inclusive and accountable governance.

The IDP is built on a firm commitment to Gender Equality, Disability, and Social Inclusion (GEDSI), and responds directly to the impacts of the climate crisis and unsustainable development, which disproportionately affect persons with disabilities (PWDs), older persons, historically underrepresented communities in urban settings, and other excluded groups. Embedding FPIC ensures that governance, climate action, and service delivery are not only technically sound but socially just, inclusive, and rights-based — helping ensure that no one is left behind.

Key FPIC Principles in IDP

Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC)1 originated as a principle of international human rights law, particularly to protect the self-determination of Indigenous Peoples in the face of land appropriation, displacement, or harmful development projects. It has since been codified in instruments like the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and adopted by multilateral institutions including the World Bank, IFC, and UN agencies.

In the Inclusive District Platform (IDP), we adapt FPIC from its original legal context into a broader framework for ethical urban governance — one that prioritizes consent, participation, and dignity for all marginalized populations in cities. Rather than treating consent as a one-time approval, FPIC in IDP becomes a continuous process of community co-ownership, especially for people historically excluded from planning and policy: persons with disabilities, older persons, youth, women, and informal residents.

Table 1. FPIC and IDP Application

When applied in urban settings, FPIC serves not only as a rights-based safeguard, but as an innovation driver — making space for ethical AI, inclusive data protocols, and community-owned civic technologies.

Communities have real decision-making power to approve, modify, or reject proposals, and consent is tracked over time.

Enabling Mechanisms

Consent alone is not enough — we need the systems that make it meaningful. This section introduces the technical and ethical enablers of IDP: inclusive data, ethical AI, accessible tech, and principles like transparency and justice.

Community-Owned Data Protocols: Communities retain control over how data about them is collected, shared, and reused, ensuring ethical data stewardship and trust.

Ethical AI and Inclusive Technology: AI tools are co-developed and transparent, using inclusive datasets to prevent bias and support equitable, community-led insights.

Washington Group Disability Questions: These tools ensure data is disaggregated by disability status, enabling visibility and meaningful participation for PWDs.

Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG)-Compliant Accessible Platforms: All digital platforms meet global accessibility standards so persons with disabilities can fully engage and access information.

Participatory Geospatial Mapping: Community members co-create spatial data to visualize land use, risks, and interventions, enabling informed and inclusive decision-making.

Disability Data and Accessibility: Gaps, Challenges, and the Case for Ethical Investment

In this context, the Inclusive District Platform (IDP) positions community-owned data, WCAG-compliant accessibility tools, and inclusive AI as more than technical features — they are political and ethical imperatives. They ensure that those who have been excluded from data narratives are now centered in how cities are built, governed, and resourced.

Despite a growing national commitment to data integration — including policies like One Map and One Data — the reality of disability data in Indonesia remains fragmented, unreliable, and poorly governed.

Currently, four main government sources hold disability-related data — Susenas and Supas (BPS), P3KE (Coordinating Ministry for Human Development and Culture), Data Terpadu Kesejahteraan Sosial (DTKS, Ministry of Social Affairs), and Registrasi Sosial Ekonomi (Regsosek, Bappenas).

These datasets are siloed, sector-specific, and have yet to consistently apply internationally recognized standards such as the Washington Group Questions on Disability Statistics. As a result, the national data often fails to capture the diversity of impairments, environmental barriers, and lived experiences — leading to incomplete and poorly targeted policies

At the same time, detailed geospatial data on accessibility infrastructure — ramps, tactile paving, accessible toilets, and inclusive public transport — is either missing or not standardized, limiting mobility and civic access for millions of Indonesians.

In stark contrast, Indonesia has invested extensively in mapping and geospatial systems for natural resource and environmental management — through initiatives such as:

It is no exaggeration to say: we know every inch of the forest better than we know the lives of people with disabilities.

This gap is not merely technical. It reflects deeper structural imbalances in how data is prioritized and governed. Indonesia has historically made massive investments in data systems for natural resources and land use: from Regional Physical Planning Program for Transmigration (RePPProT), Land Resource Evaluation and Planning Project (LREP), Marine Resource Evaluation Program (MREP, 1993-1998), Marine Coastal Resource Mapping Project (MCRMP), Coral Reef Rehabilitation and Management Program (COREMAP, 2014-2022), Land Administration Project and the latest Complete Systematic Land Registration Program (PTSL) initiative.

Yet these systems have not always ensured accountability or public trust. In fact, they have been widely criticized for:

And continuing deforestation, contradicting their stated sustainability goals

These failures reveal the consequences of weak data governance — where technical systems are developed without ethical safeguards, inclusive participation, or community consent.

This is precisely why the IDP anchors itself in Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC). FPIC is not only a safeguard for vulnerable communities — it is a necessary framework for ethical data systems, equitable planning, and resilient governance. It ensures that those who have long been excluded — especially persons with disabilities and informal residents — are counted, respected, and empowered to co-create their urban futures.

Values Anchoring the Model

The Inclusive District Platform (IDP) is grounded in four core values that guide how FPIC is practiced and embodied. These values are not abstract ideals — they are practical, normative principles that shape daily decision-making, data use, and governance approaches:

Transparency and Accountability. Every process is documented, traceable, and open to public review — ensuring trust, minimizing the misuse of power, and strengthening democratic oversight.

Inclusion and Social Justice. The platform prioritizes the voices, rights, and lived experiences of historically excluded groups — including persons with disabilities, older persons, women, youth, and informal urban residents.

Trust and Collective Agency. Communities are not just consulted — they co-govern. By actively participating in decision-making, they build shared ownership over civic and development outcomes.

Sustainability and Resilience. Decisions rooted in consent, equity, and long-term thinking lead to solutions that endure — and empower communities to adapt, respond, and thrive.

Living Laboratories for Inclusive Transformation

Innovation without grounding risks exclusion. That’s why the IDP has been rooted in three urban districts as real-world laboratories — where communities, governments, and partners co-create and test what inclusive governance can look like in practice.

The IDP began in 2022 in Sumur Bandung District, Bandung, through a bottom-up initiative involving over 20 organizations and community groups. These actors represent a wide spectrum of expertise — from disability inclusion, urban planning, and gender justice to data science, academia, youth organizing, and cultural heritage — making it a truly cross-sectoral and community-rooted platform.

Building on this momentum, the IDP will be expanded to two additional pilot districts: Semarang Tengah (Semarang) and Jetis (Yogyakarta). In each location, the approach will be adapted to fit the local social, cultural, and institutional context, while upholding the shared principles of FPIC, GEDSI, ethical AI, and inclusive governance.

These three districts serve as living laboratories where participatory governance is practiced in real-time — offering a model that can be scaled across Indonesia and also shared with other cities in Asia and Africa through South-South learning and capacity building.

FPIC as a Catalyst for Civic Technology and Social Impact Investment

Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) is more than a safeguard — in the Inclusive District Platform (IDP), it is a driver of innovation that transforms the governance process into a foundation for inclusive civic technology, ethical data systems, and social impact investment that centers vulnerable communities.

FPIC invites a paradigm shift: from extracting consent to co-creating solutions that are built with the community, by the community, and for lasting equity.

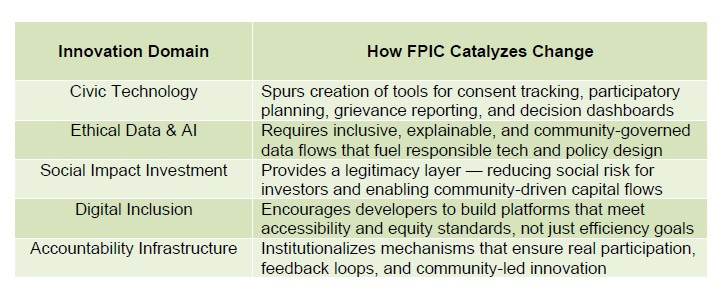

Table 2. FPIC as Catalytic Changer

By embedding FPIC, vulnerable communities (e.g. PWDs, older persons, women, youth, Indigenous peoples) are no longer just recipients of innovation — they become governors of their own data, agents of design, and leaders in civic transformation.

“FPIC is not just a right. It’s a launchpad for ethical innovation and inclusive investment — where the consent of communities fuels technology that serves justice, equity, and resilience.”

While FPIC is rooted in the rights of Indigenous Peoples, the principles of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent—consent before action, transparent information, and self-determined participation—are increasingly relevant to urban settings. In cities, historically excluded communities, including persons with disabilities, older persons, youth, and informal residents, often face systemic exclusion from planning and data governance. By adapting FPIC to these urban realities, the IDP seeks to ensure that no one is left behind in shaping inclusive, just, and resilient local development.

From Consent to Change

“Together by Consent” is more than a title — it is a commitment to ethical innovation and inclusive investment.

This is more than a concept as well — it is a shift in how we build trust, scale innovation, and invest in communities. As we close, this section reflects on what FPIC means as a platform for future-facing, community-led transformation.

By integrating Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) into the Inclusive District Platform, we are building local systems where communities don’t just participate — they lead. This platform reimagines urban governance as a shared process, where data is co-owned, trust is institutionalized, and no decision moves forward without consent.

From Bandung to Yogyakarta, we are piloting a model that links civic technology, ethical AI, and social impact investment — driven by those who have too often been left out.

FPIC is not only a safeguard — it is the foundation for building collective capacity, innovation, and justice from the ground up.

#ConsentToCreate #SocialInvestment #FPIC #InclusiveGovernance #EthicalTech #CommunityLed #TogetherByConsent #SouthSouthSolidarity

Suggested Reference: (1). United Nations General Assembly (2007). United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). A/RES/61/295 (2). World Bank. (2018). Environmental and Social Framework: Setting Environmental and Social Standards for Investment Project Financing (3). International Finance Corporation (IFC). (2012). Performance Standards on Environmental and Social Sustainability (4). United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII) (2021). Free, Prior and Informed Consent: Practical Guide (5). Whaites, A. (2016). Achieving Governance Reform through Adaptive Programming. OECD-DAC GovNet (6). Cornwall, A., & Gaventa, J. (2001). From Users and Choosers to Makers and Shapers: Repositioning Participation in Social Policy. IDS Bulletin.