If we want to talk seriously about sustainability, resilience, and social justice, then we need to start from the ground—quite literally—from our districts. Sumur Bandung, a district in the heart of Bandung City, is more than a geographic unit; it’s a living example of how the challenges of climate change, social exclusion, and unsustainable systems intersect in everyday life. It’s also where a different future is possible—through data-driven, inclusive, and participatory models like the Inclusive District Platform (IDP).

This article offers a critical assessment of the supply chain of sustainable production and consumption (SPC)—through the lens of Gender Equality, Disability, and Social

Inclusion (GEDSI). Using the example of Sumur Bandung District, it explores how existing waste, water, and sanitation systems remain fragmented, exclusionary, and unsustainable.

The core argument is simple: without GEDSI, sustainability is incomplete—and often unjust.

In the end, what this all reveals is a deeper truth: the supply chain of sustainable production and consumption cannot be truly sustainable unless it is inclusive. Sumur Bandung shows us both the urgency and the possibility—if we start by centering GEDSI as the foundation of how we plan, govern, and build systems for the future.

A Crisis of Sytems, Not Just Waste

According to data from the Central Statistics Agency (BPS) of Bandung City in 2023, Bandung produces 1,594.18 tons of waste per day. The majority is food waste and leaves—709.73 tons daily (44.5%), followed by plastic waste at 266.23 tons (16.7%), and paper waste at 209.16 tons (14%)1.

These figures are staggering—and they underscore a deeper crisis: our city’s systems are designed to dispose, not to reuse, reduce, or reintegrate. And critically, they do not include or serve the people most affected: the elderly, persons with disabilities, and low-income residents who live alongside this waste or informally sort it for income—often without recognition, protection, or opportunity to participate in systemic solutions.

City of Bandung has at least three major waste crises over the last two decades. Despite the enactment of Law No. 18/2008 on Waste Management—which mandates a shift to circular economy principles—the city continues to struggle with domestic waste issues. The law's spirit of promoting sustainable production and consumption has yet to translate into full implementation.

At the grassroots level, waste management interventions have not fully penetrated the supply chain from households to temporary storage (TPS) and final disposal. Programs like Kang Pisman (Separate and Utilize) and Waste Banks, though well-intentioned, have largely been top-down and disconnected from daily practices. They have failed to produce significant change in high-waste generating areas such as Sumur Bandung.

Even more critically, the role of elderly and disabled residents as contributors to the circular economy has been overlooked. Opportunities to involve them in various segments of the waste supply chain—from collection to processing—remain untapped.

Beyond waste, the lack of inclusive systems is evident ini other issues:

Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR): Despite seismic threats like the Lembang Fault, there is no disaster risk mapping at the sub-district level. Vulnerable groups, especially those with sensory, mental, or mobility challenges, are left out of emergency planning.

Water and Sanitation: Most PWDs and elderly individuals still lack access to sitting toilets or safe handrails. The nearby river continues to function as an informal sewage outlet, while communal WASH programs often face land constraints.

The problem is clear: without disaggregated, ground-level data, interventions miss the mark. Mapping is not just technical—it’s foundational to equity.

Figure 1. Sumur Bandung’s daily life: where health services, informal work, and waste collide in one street. This is the frontline of sustainability—and inclusion (taken on 8 April 2025)

The supply chain of sustainable production and consumption cannot be truly sustainable unless it is inclusive. Sumur Bandung shows us both the urgency and the possibility—if we start by centering GEDSI as the foundation of how we plan, govern, and build systems for the future

Making Diagnosis to Design: Building from Within

Through the IDP, we are seeing a shift. With geospatial data, household surveys, and mapping of vulnerable groups, the district is becoming a lab for systemic change. We now know how many mosques, churches, and viharas exist—76 mosques alone2. This matters because these aren’t just spiritual centers; they are literacy hubs. Ustadz and marbot, teachers and caretakers, can lead climate and WASH (Water, Sanitation, Hygiene) Sumur Bandung’s daily life: where health services, informal work, and waste collide in one street. This is the frontline of sustainability—and inclusion literacy campaigns that touch hearts and habits.

The IDP offers a better way: community ownership. Using inclusive mapping, citizen-led planning, and participatory budgeting, the IDP model moves beyond consultation toward shared governance. This approach includes:

Empowering faith leaders, teachers, and grassroots advocates as climate educators

Building neighborhood ownership of sanitation and DRR infrastructure

Ensuring women, PWDs, and elderly are not just “included” but central

Solving these complex challenges demands systemic action:

Governments must legislate, fund, and monitor inclusive systems

Private sector must go beyond Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and invest in equitable supply chains

Faith institutions and schools must shape behavior and civic literacy

Communities must co-create, not wait. This is not an act of charity - It is a matter of equity and governance.

Data and Design: Accessibility as a Right

Information is power, but only if people can access it. That’s why all public data, resources, and digital platforms under IDP must comply with the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG). People with visual, cognitive, or motor impairments have the same right to understand, decide, and act. WCAG isn’t an afterthought—it’s a foundation.

Current government data systems are fragmented across four major ministries and institutions: the Central Statistics Agency (BPS), the Integrated Social Welfare Data (DTKS) managed by the Ministry of Social Affairs, the Regional Socioeconomic Registry (Regsosek) under Bappenas, and the Extreme Poverty data under the Coordinating Ministry for Human Development and Culture. However, these systems have not fully adopted the internationally recommended Washington Group Questions on Disability Statistics, making it difficult to align with global standards or draw comparisons across countries.

In addition, the government’s One Map and One Data3 policies focus primarily on inter-agency coordination rather than public accessibility or validation from non-government sources. This has created a significant gap between top-down data and community realities. For instance, in Sumur Bandung, people with mental and intellectual disabilities remain largely invisible in official data sets.

People with disabilities must not only be seen as users of data and services, but also as stakeholders and decision-makers. Accessible, open, and interoperable data is an entry point for inclusive governance. Data must reflect lived realities, and the process of collecting it must engage the very people it aims to represent.

The transformation of Sumur Bandung—and districts like it—requires a coordinated effort by all sectors of society. Government actors must embed GEDSI principles into laws, budgets, and enforcement mechanisms. The private sector must move beyond compliance and align their operations with inclusive and sustainable practices. Religious leaders and educators must become civic educators who frame sustainability and justice as moral imperatives, not optional extras.

Figure 2. IDP began as a pilot in Sumur Bandung (green marker) and is expanding to targeted districts across Indonesia (red markers) as resources and momentum build. This evolution illustrates how inclusive design, data, and participation can scale from local to systemic transformation

The IDP was first conceptualized and piloted in Sumur Bandung District, where it tackled the intersection of WASH, waste, mobility, and inclusive governance. Building on its early lessons, the platform is now being scaled to other districts across multiple provinces, as indicated by the visual framework. This evolution reflects not just programmatic growth—but a shift in how local governance, spatial justice, and sustainability are approached from the ground up.

The IDP’s five foundational pillars—data-driven policy, transformation hubs, participatory planning, open platforms, and sustained engagement—are adaptable to different localities, making it a nationally scalable model rooted in local ownership.

No single actor can solve what is fundamentally a systemic issue. Inclusive urban transformation depends on breaking silos between policy, planning, and people. The Inclusive District Platform is not just a governance tool—it’s an invitation to rewrite the rules of development through equity, resilience, and collective accountability.

Scaling Systems, Not Projects

Sumur Bandung is just one of 30 districts in Bandung City. In 2025 with an annual city budget of nearly IDR 8 trillion4 (approximately USD 470 million), the estimated cost of IDR 12–20 billion (USD 800,000 to 1.3 million) per district for inclusive WASH and waste system upgrades is entirely feasible. If phased strategically—starting with the most vulnerable districts—this model can scale citywide within 5 to 6 years, absorbing only less than 1% of the city's budget. This is not an extraordinary cost. It is a strategic, long-term investment in the city’s equity, sustainability, and climate resilience.

Figure 3. The IDP began as a pilot in Sumur Bandung District (green marker) and is expanding to targeted districts across Indonesia (red markers) as resources and momentum build. This evolution illustrates how inclusive design, data, and participation can scale from local to systemic transformation

IDP was first conceptualized and piloted in Sumur Bandung District (2022-2024), where it tackled the intersection of WASH, waste, mobility, and inclusive governance. Building on its early lessons, the platform is now being scaled to other districts across multiple provinces, as indicated by the visual framework. This evolution reflects not just programmatic growth—but a shift in how local governance, spatial justice, and sustainability are approached from the ground up. The IDP’s five foundational pillars—data-driven policy, transformation hubs, participatory planning, open platforms, and sustained engagement—are adaptable to different localities, making it a nationally scalable model rooted in local ownership.

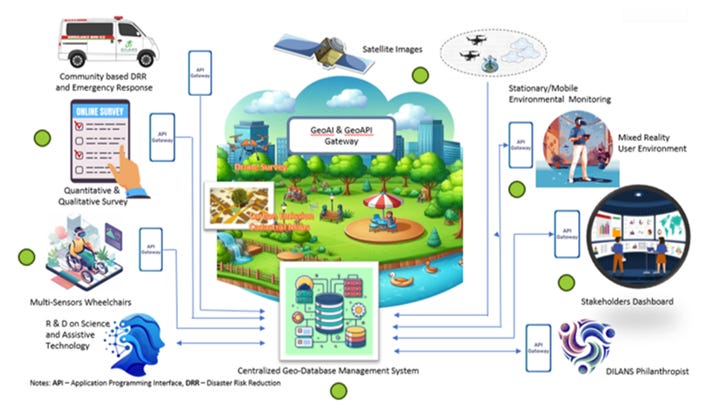

Technology will play a critical role in scaling and sustaining inclusive systems. From geospatial vulnerability mapping and mobile sanitation tracking apps, to assistive technology and digital literacy tools, innovation must serve inclusion. Digital systems can help identify gaps, streamline resource allocation, and amplify citizen voice—particularly for persons with disabilities and the elderly. But this must be technology designed for dignity, not just efficiency.

Scaling inclusive systems cannot depend solely on public finance. A mix of municipal budgets, blended finance, cooperative ownership, community contributions, and philanthropic investment can collectively mobilize resources. Cooperatives, for instance, can operate inclusive recycling or WASH service centers; CSR funding can pilot new models; and provincial or national funds can match city-level efforts. With the right financial architecture, inclusive systems are not just viable—they’re catalytic.

Sustainability is not just about resources—it is about the systems we build to manage those resources collectively. Engineering inclusive supply chains at the district level—through waste, water, food, and services—is not a hypothetical exercise. Through the IDP, it becomes a practical, participatory model that includes citizens, persons with disabilities, the elderly, and even informal sectors often left out of formal governance.

Persons with disabilities and the elderly must be recognized as active subjects, not passive recipients. Their roles must evolve from being ‘served’ to becoming co-creators, contributors, and workers—supported by technology and environments designed through universal design principles

The IDP is not merely a platform—it can become what Nobel laureate Elinor Ostrom called a commons: a shared space governed by rules co-created by the people who depend on it. If IDPs apply Ostrom’s eight principles5—from clearly defined boundaries to collective decision-making and accountability—they can serve as resilient, long-lasting social and governance ecosystems.

The Future We Build, Together

Sumur Bandung may be one district, but it holds the blueprint for inclusive urban resilience. GEDSI, climate justice, and sustainable consumption are not separate challenges—they are parts of the same systemic equation. The state, private sector, faith leaders, civil society, and most importantly, communities themselves, must join forces—not just in responding to problems but in owning solutions. The IDP is not the end. It’s the beginning of a new social contract—one that starts in our neighborhoods, with the people too often left behind.

To truly transform urban systems, we need more than participation. We need ownership. The IDP provides a way for residents, especially marginalized ones, to move from being data points to decision-makers. It shows us that communal waste centers, accessible toilets, and disaster-ready infrastructure only work when communities co-create them—and when women, PWDs, and the elderly are central, not peripheral.

Based on preliminary modeling using unit costs for inclusive toilets, drainage, water points, and community engagement, a full-scale inclusive WASH and waste system for Sumur Bandung is estimated to cost USD 800,000 to 1.3 million. This is not a cost—it is an investment in equity, dignity, and resilience, and a foundation for building lasting systems of care and inclusion at the neighborhood level.

In the end, this is not only about infrastructure or investment—it’s about how we design systems, who we include, and how we govern the spaces we share.The Inclusive District Platform is more than a policy tool—it’s a social and institutional design rooted in equity, local knowledge, and collective stewardship. When GEDSI principles guide supply chains, and when citizens shape the commons, we don’t just solve problems—we build the foundations for a just and sustainable future.

True inclusion is not just about participation—it’s about shaping systems that adapt to people, not the other way around.

The Inclusive District Platform is more than a policy tool—it is a social and institutional design rooted in equity, local knowledge, and collective stewardship.

Crucially, in every stage of the supply chain—from design and decision-making to monitoring, implementation, and maintenance—persons with disabilities and the elderly must be recognized as active subjects, not passive recipients.

Their roles must evolve from being ‘served’ to becoming co-creators, contributors, and workers, where appropriate, based on their strengths, preferences, and capacities.

To enable this, both technology and working environments must be designed following universal design principles, ensuring accessibility, safety, and usability for everyone from the start.

Key Takeaways

To summarize what this approach to inclusive systems offers, here are six core insights:

Sustainability is systemic. Waste, WASH, DRR, and data are all part of interconnected supply chains that must be designed with inclusion at the core.

GEDSI is not optional. Without the participation and leadership of women, persons with disabilities, and the elderly, sustainable development remains unjust and incomplete.

Districts are the scale of transformation. The Inclusive District Platform (IDP) shows how local governance, community engagement, and data-driven planning can converge to produce scalable, long-lasting change.

Technology must serve equity. Digital tools, accessible data, and inclusive design are critical to bridging service gaps and amplifying community voice.

Investment must be catalytic. Public budgets, blended finance, and cooperative models can work together to fund resilient, people-centered infrastructure—not as charity, but as smart governance.

The IDP is a modern commons. Inspired by Ostrom’s principles, it offers a governance model rooted in participation, accountability, and shared stewardship of place and future.

Inclusion must be designed, not assumed. Technology and workspaces must follow universal design principles, enabling PWDs and the elderly to participate fully and equitably across systems.

The IDP is not merely a platform—it can become what Nobel laureate Elinor Ostrom called a commons: a shared space governed by rules co-created by the people who depend on it.

#InclusiveByDesign #UrbanJustice #SocialInclusion #ClimateResilience #GEDSI #SustainableDevelopment #IDP #InnovationForAll #PeopleCenteredDesign #BersamaKitaBisa #DisabilityInclusion

Indonesia’s “One Map Policy” (Perpres No. 9/2016) aims to unify all geospatial data under a single reference map to reduce overlaps in land use and governance. The “One Data Policy” (Perpres No. 39/2019) complements this by standardizing data formats, improving interoperability, and enhancing coordination across ministries. Both policies are designed to support evidence-based planning and public transparency. Source: Bappenas – Satu Data Indonesia

https://jabarprov.go.id/berita/apbd-kota-bandung-2025-resmi-ditetapkan-16511 (accessed on 12/04/2025)

Nobel laureate Elinor Ostrom in Governing the commons: The evolution of Institutions for Collective Action (1990) identified eight core principles for long-enduring governance of shared resources (“commons”): Clearly defined boundaries – who has access is known; Rules tailored to local needs; Collective decision-making – those affected participate in rule-making; Monitoring – overseen by community members; Graduated sanctions – proportional responses to misuse; Conflict-resolution mechanisms – accessible and low-cost; Recognition of rights to organize – by external authorities; Nested enterprises – activities are organized in layers for large systems.